Written by Anushka Bose

The word bacteria typically has a negative connotation and is often associated with devastating infections. In reality, some forms of bacteria can sometimes be good for you. In fact, it’s being clinically examined to treat mental health conditions. Last month I spoke with Dr. Christopher Lowry, an Associate Professor in the Department of Integrative Physiology and Center for Neuroscience at the University of Colorado Boulder, who talked about this idea in depth.

Dr. Lowry spoke at our TEDxMileHigh: Vision event, and his talk focused on how bacteria can provide us with various benefits for physical and mental health. Follow our discussion about how bacteria, found in food, nature, and in our municipal water supply can create a diverse gut microbiome that can reduce our inflammatory stress response.

Watch Chris Lowry’s TEDxMileHigh talk from TEDxMileHigh 2020 Vision Conference.

A Conversation with Dr. Chris Lowry on Gut Bacteria and Mental Health

Thank you so much for making time, Dr. Lowry. Your talk mentioned that some bacteria are our “old friends.” What exactly do you mean by that?

So, early mammals were small creatures that lived under the soil, which means for millions of years, they co-evolved with soil bacteria by breathing in and eating soil. They are our old friends in the sense that humans have co-evolved bacteria in our environment, and these “old friends” can communicate with our brains through the microbiome-gut-brain axis.

There are many benefits of bacteria that we can talk about, but my talk was promoting the idea that bacteria are useful in reducing the inappropriate inflammation in our bodies that shows up in a variety of stress-induced mental health conditions.

You studied the role of bacteria in military veterans with PTSD and mild traumatic brain injury at the VA Institute, right?

Yes, we partnered with Dr. Lisa Brenner at the Rocky Mountain MIRECC for Veteran Suicide Prevention, in 2016. We conducted clinical trials with U.S. military veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD and mild traumatic brain injury and gave them a live bacterium with anti-inflammatory properties daily for eight weeks.

We then brought them into the research laboratory and exposed them to a psychological stress paradigm called the Trier Social Stress Test. Those that received the anti-inflammatory bacterium showed reduced stress reactivity and a strong trend for reduced inflammation. Although larger studies are needed, it supports that idea that exposure to bacteria with anti-inflammatory properties can promote stress resilience.

How close are we to having this kind of research on the market?

It is within reach. The challenge is, with a drug treatment, there are regulatory requirements, as there should be. Which is why I am promoting a more accessible way of going about increasing exposures to bacteria for optimal health—one that just calls for a trip to the grocery store, drinking municipal water (if clean), and getting out in nature.

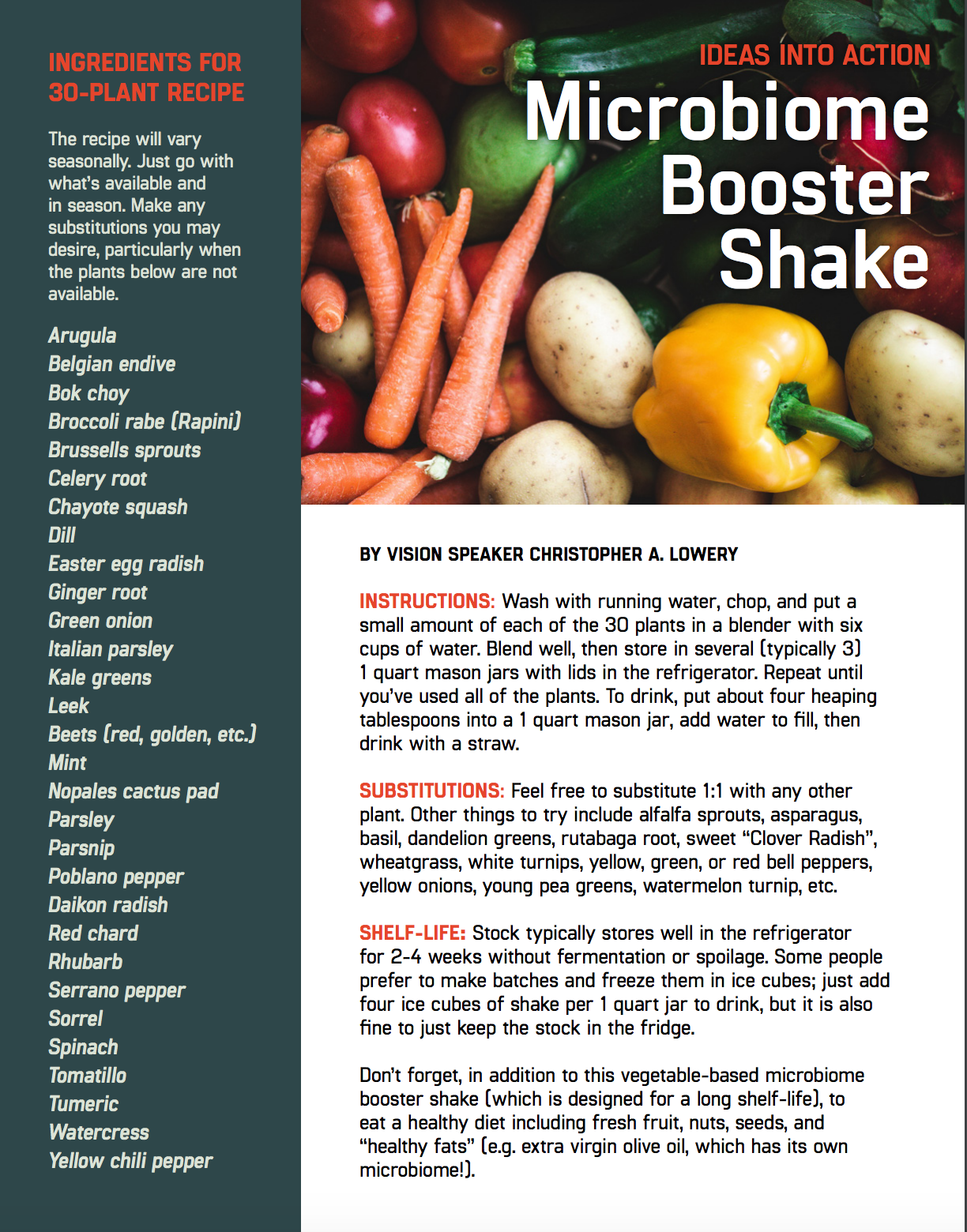

Let’s get into your 30-day plant-smoothie. Can you share the message you are trying to convey?

The microbiome booster shake is meant to diversify your gut microbiome. The idea is that the more diverse your microbiome is, the more resilient you are. Different types of plants provide different types of bacteria. Take spinach — it contains more than 800 different species of bacteria on and inside the plant.

Based on data from the American Gut Project, survey respondents were asked the question, “In an average week, how many different plant species do you eat?” Answers ranged from 0 to over 30 plants a week. Those who reported eating a higher diversity of plants had a more diverse gut microbiome. I thought, what would happen If I consumed 30 different plants a day? It would be similar to eating a whole forest, or farm, each day.

Your smoothie is just vegetables, not other plant-based foods. What’s the reason behind excluding fruits?

The smoothie I am suggesting is just vegetables, not fruits because I don’t want sugar that can ferment.